Netti Remembers

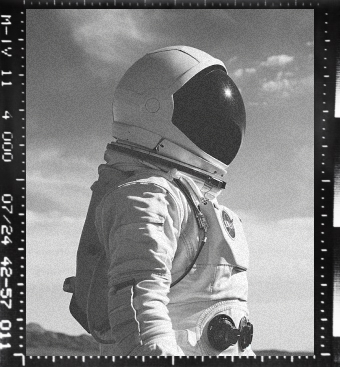

Drawn out of her repose by the loud sound of the life-support system shifting to its nocturnal mode, Netti became aware of her surroundings and the photograph in her hand. The view from the window in her cabin revealed the billowing plains of Terra Sirenum in the southern hemisphere of Mars. She had stopped to rest on her long journey, now hundreds of kilometers from her home base and the ring of terrestrial garbage that surrounded it. Here, there was no sign of the scars humans had rendered on the planet. The horizon looked boundless and pristine. Beyond the requisite supplies and some navigation instruments, she had brought very little with her—a photograph, a book, and a postcard from her mother. Her home was now the small exploration rover, sculpted from glass and steel, resting on its four wheels. The cabin was cluttered but not uncomfortable. She had enough space to straighten her body out to sleep and to change into a space suit. She could even do some stretching exercises.

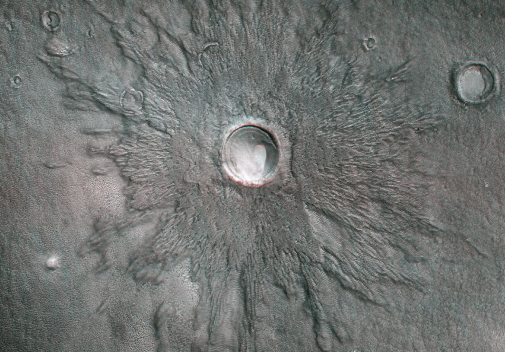

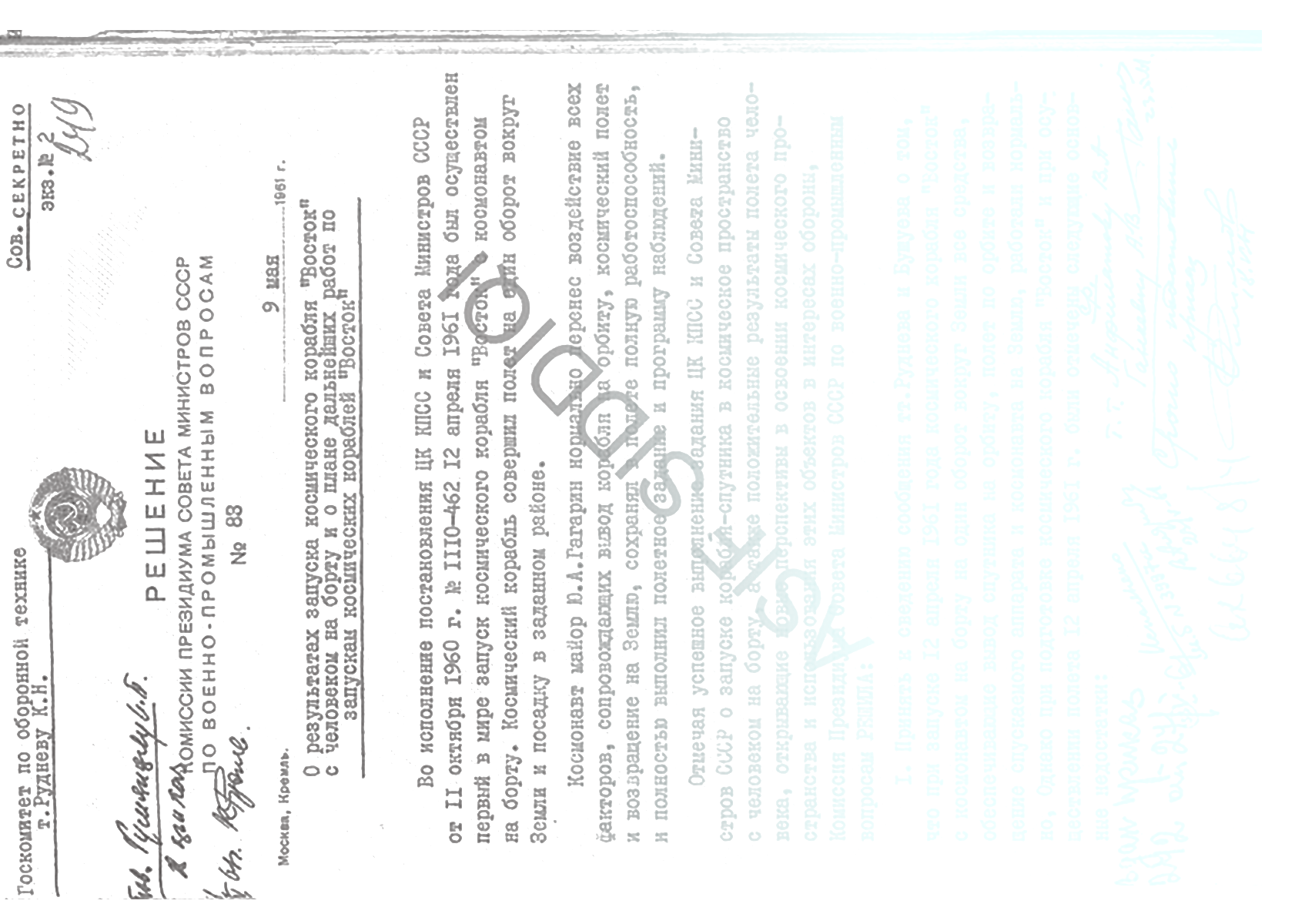

The creased photograph in her hand was technically a printout. It seemed to show a black-and-white image of static from a malfunctioning TV set, punctuated by a thick horizontal white stripe that cut across the picture. One could be forgiven for mistaking it for an ultrasound mangled by a printer. But this picture was a matter of historical record—the first image ever sent back from Mars to human eyes, dispatched from the Mars-3 probe, all the way back in 1971.

The story of this probe had remained with her from her childhood, an obscure footnote in the history of Mars that few if any still cared about. As a child, her mother had presented her with many books on the red planet, including one about the forgotten Georgii Babakin, the man who had designed Mars-3. As a child, Babakin had found refuge in science fiction, a world away from the many traumas of his childhood, including his father’s death in World War I. His tragically short life, as it arced from his modest beginnings in suburban Moscow on a trajectory toward Mars had ended with that impenetrable photograph. To some, the picture’s garbled image was simply the artifact of a failed camera. To others, it showed the ghosted visage of an alien planet: if one looked hard enough, it would reveal some ineffable truth. Netti hoped for the latter.

Netti found herself drawn to Mars not because it was so ubiquitous in humans’ dreams of space but because it seemed to be the graveyard for so many hopes. In high school, when her creative writing teacher had challenged students to write a fictional passage about a place without witnesses, she instinctively knew what to write: a speculation about that first garbled photograph from Mars sent back by Mars-3. She had written:

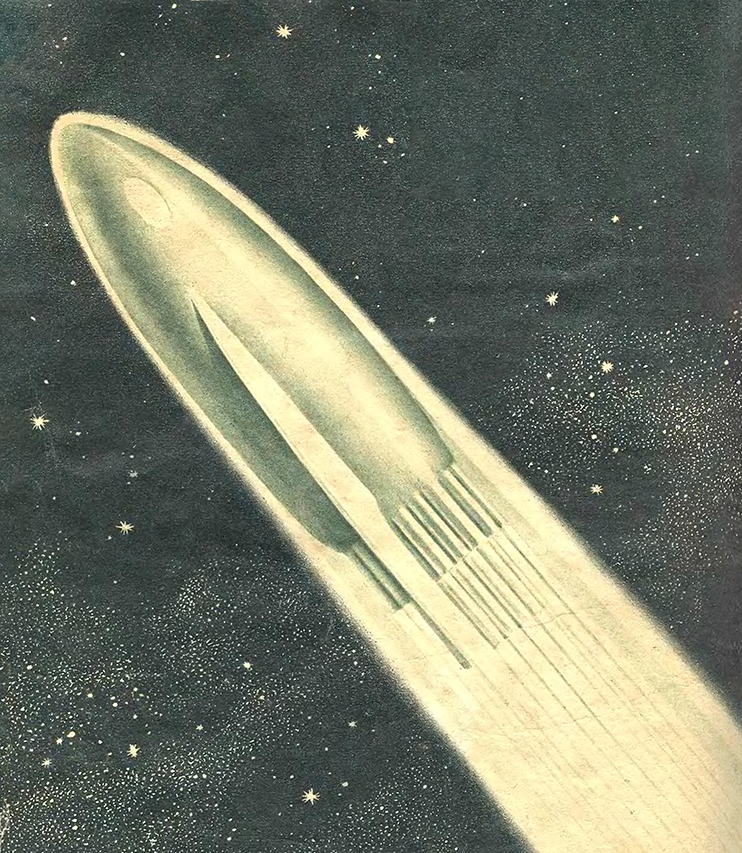

Mars is not calm today. A turbulent dust storm rages over a considerable portion of its surface, as tiny dust particles cloud visibility in every direction. Through this maelstrom, an 800-lb object hurtles into the Martian atmosphere at a speed of nearly 13,000 miles per hour. In the four-and-a-half billion years of the planet’s existence, there has been nothing like this—a tiny speck rushing down to the ground, not by accident but by intent.

On the object itself, a sensor soon activates a braking parachute and then a huge, main parachute, slowing it down. A heat shield flies off its base. At about a hundred feet above the foreboding surface, a gunpowder rocket fires to slow the object down further as it descends to the surface, now moving gingerly toward the ground. Covered in a thick layer of foam plastic, the object hits the surface and bounces a few times before coming to rest, now released from its protective covering. On the Martian terrain, the object, resembling some half-finished design for a crab-like robot, comes to life as various mechanical arms and levers move into position to face the surface, ready to study the soil and the surrounding air. Because of the oppressive dust storm, visibility in all direction is compromised. Yet, ninety seconds after landing, the object deploys a camera and begins scanning the horizon to record and then dispatch to its creators the first picture ever taken on Mars.

After transmitting for about 20 seconds, the camera stops working. The fierce dust storm has caused a coronal discharge shorting out all the electronics. Back on Earth, what is received is a strange, grainy image with static and no discernable landmarks. Scientists pore over this impenetrable picture, but there is nothing to see, they say. The mission is forgotten.

Before her departure for Mars to work as a mining engineer for the company, Netti had managed to make contact, through friends, with the Russian institute that had stored the raw data for that image. To her delight, they had been able to reconstitute the best image available. But even the image at its best only satiated her curiosity, now bordering an obsession. She had printed it out and carried it with her on her excursions on the Martian terrain, often staring at it mutely to discern some inkling of the mystery of this very first image from the surface of Mars.

Haunted by incompleteness, the image, and its confusing aura, seemed to become more powerful, mysterious, and stranger the more she looked at it. If a computer could magically fill in the gaps, reconstitute the pixels, and render the missing colors, what would she see? Would she see a different history, perhaps a secret history of Mars, lost to the archive, one that had disappeared, victim to our obsession with success and teleology? If one could render this image legible, would it reveal moments of a history that once offered a viable and alternative cosmic imaginary? One that was now completely erased in both history and historiography by libertarian-minded Silicon Valley billionaires who, consciously or not, drew on the intertwined histories of colonialism and capitalism to imagine their version of Mars?

Perhaps there were answers to be found in the photograph, the book, and the postcard.

A Secret History in Three Acts

Act I: Red Star

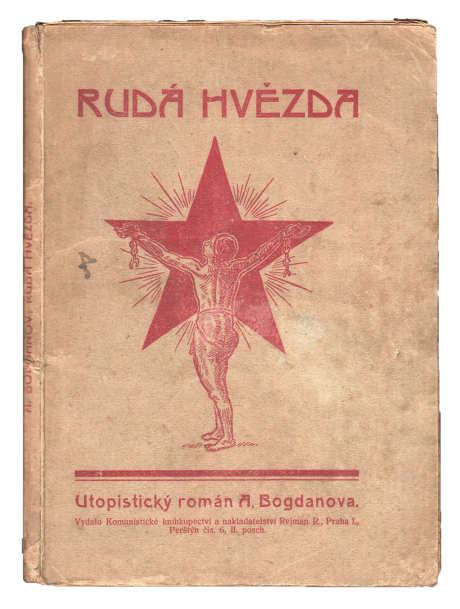

The book that Netti had tucked under the dashboard, with the evocative title Red Star, had served as a distraction during her rest periods. She had known, of course, that her mother had named her “Netti” after a character in the book, but throughout her life, she had resisted reading it. Published in 1908, exactly a century before Netti’s birth, Red Star (or Krasnaia zvezda in its original Russian) was perhaps the most famous science fiction novel published in the Russian language. Throughout her short life, many would ask Netti about her unusual name, and some, who had read Red Star, would ask about the novel. She would answer gamely, yes, her parents had appropriated the name from the novel, written by the famous Bolshevik, avowed communist, and Lenin’s comrade-in-arms, Aleksandr Bogdanov. This would be followed by some cursory jokes about socialism, workers’ rights, and alienation from the means of production—ideas that seemed as illusory as living on another planet might have once seemed. But here she was, living and breathing on Mars. So perhaps, those socialist ideas that haunted her namesake could be restored from the footnotes of history to its main text?

Netti knew very little of Bogdanov’s story when she left for Mars but over the months she had learned a lot more. Her book included a short biography of the author, and she began to feel a sense of familiarity with both his life and his fiction. As she dozed off, her thoughts drifted to what she had just read.

He was born under the name Aleksandr Malinovskii in 1873 but adopted his wife’s name, Bogdanov, as a gesture of equality. Later, he became a key actor and occasional rival to Vladimir Lenin in the Bolshevik Party. A colorful figure who wrote as much about Marxist ideology as about the future of science and technology, Bogdanov was captivated by the planet Mars. He wrote a number of works of speculative fiction, the first of which was Red Star; the title was a double allusion to both the red planet and the “red star” insignia of the Soviet Red Army.

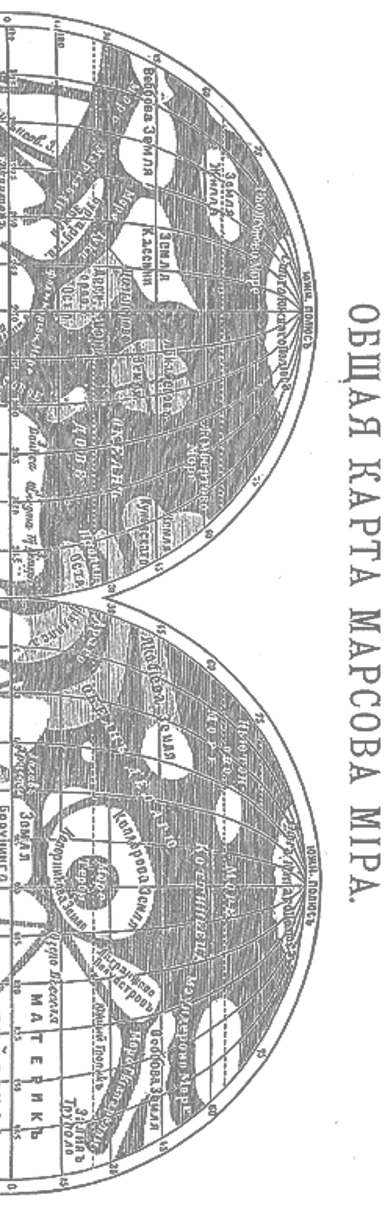

The book was deeply shaped by contemporary forces in the early 20th century, including the beginnings of industrialization in Russia, the 1905 Revolution against Czarist rule, the proliferation of utopian science fiction, both Western and homegrown, and of course, the international publicity surrounding the discovery of “canals” on Mars popularized by American astronomer Percival Lowell.1 At one level the novel was a utopian meditation on the combined power of socialist thought and modern science to transform the social order. The main protagonist of the novel, Leonid (or Lenni), who like Bogdanov was a scientist-turned-revolutionary, visits Mars upon the invitation of Menni, a Martian who visits Earth.

On Mars, Lenni finds a socialist utopia where workers live and work together and where job assignments are based on societal demands rather than any capitalist forms of extraction. Those who do not wish to work do not. The poison of nationalism is absent on Mars, with ethnic divisions no longer a vexing, divisive issue. The contradictions between the urban and the rural—a central concern of Marxists at the turn of the century—are resolved in the creation of “in-between” worlds where people live and work. Apartments are logically connected to laboratory workspaces (often underground) such that inhabitants valorize one over the other. Everything, including work, is highly automated. On Mars, though, there was no manifestation of scientific management practices like Taylorism, the uniquely American system of mass production wherein the smallest task of a worker is broken down to its most efficient form. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Bogdanov found Taylorism deeply exploitative. Social development is geared towards an appreciation of the value for the whole rather than individual gain. In fact, creativity at all levels is a collective force. This was full-blown socialism on Mars, but in the words of one historian, “updated by means of contemporary scientific and organizational discoveries.” 2

All of this resonated deeply with Netti who felt utterly disconnected from the clinical and mechanical nature of her life and work on Mars, which to her seemed less a planet than a corporate brand, spewing out garbage onto the Martian surface. If work left her enervated, she found solace in Bogdanov’s imagination. What Netti found most seductive about Bogdanov’s book was that it insisted on a form of generosity and fairness to all, undergirded by concepts of self-sacrifice and egalitarianism. At the same time, Bogdanov resisted the urge to valorize a dogmatic form of a socialist utopia, warning against the many problems inherent in trying to construct a society on Mars—including the dangers of nuclear power, the destruction of the natural environment of Mars, and the challenges of what might today called bioethics.3

Sitting in her rover at the edge of Newton Crater, a 180-mile geological formation south of the Martian equator, Netti rehearsed these aspects of Bogdanov’s novel. But there was one other dimension of the book—its gender politics—that had drawn her attention in the past few months. The character she was named after, Netti, is initially introduced as male but then is rendered female in the latter part of the novel when she becomes Lenni’s love interest. This transformation is treated without any special consideration as if the transition was emblematic of a deeper form of normative fluidity in Martian socialism and impossible within terrestrial capitalism. For Netti, these ideas were enormously comforting and led her to the radical tracts of Bogdanov’s friend and Bolshevik feminist Aleksandra Kollontai who believed that an ideal form of socialism could not be attained absent radical shifts in attitudes to sexual difference.4

As Netti finally dozed off, the postcard fell out of her hand and onto the floor of her cabin. Sent long ago by her mother, the scribble simply said “Onwards, to Mars!” The picture on the back showed a slim middle-aged man with a mustache and a beard, sitting at his desk, legs crossed, staring intently at the camera: who was this Man from Mars?

Act II: Onwards, to Mars!

In Riga, Latvia, on the night of August 11, 1887, spectacular meteorites streaked like trails of white rain across the night sky. The whole city came alive with thousands of people lining the Daugava River to see reflections of the star-like trails on the black water. On the same night, a few miles away, Fridrikh Arturovich Tsander was born to a middle-class family. As he grew up, he heard about this meteor shower so often that it was as though he’d witnessed it himself. In fantasy intertwined with lived experience, he recalled, many decades later, when he was almost forty years old, that “this phenomenon… left a deep mark on my imagination [and] since childhood I loved to stand at the window and look at the stars on dark winter evenings.”5

Already as a child, Tsander was captivated by the cosmos. Raised on a diet of science fiction, including Russian translations of Jules Verne, Tsander soon grew into adulthood compelled by the call of outer space. A Russian writer noted, “[F]or most people, earthly life overshadows the life of the cosmos, but for Tsander, the life of the cosmos overshadowed his entire earthly life.”6

After graduating with honors from the Riga Polytechnic Institute at the age of 27, Tsander ended up working as an engineer at an airplane factory in Moscow, but his mind was clearly elsewhere. When he and his wife, Aleksandra, who worked in the canteen at the factory, had two children, a boy and a girl, Tsander insisted on naming them Astra and Mercury. Astra would write later that her father was unusually kind and forgiving and tried to impart these values to his children: “People are not evil,” he told Astra, “people deep down are naturally good.”7 But, he cautioned, there would be people who would not understand his obsession with space, that they would judge them and so they should be patient.

The Tsander family’s home life was occupied by all manner of seemingly mad experiments that anticipated future flights to Mars. In 1916, at his home, Tsander built a lightweight greenhouse that would supply fresh vegetables and absorb carbon dioxide for travelers in outer space. Without a trace of irony or self-consciousness, Fridrikh would talk endlessly about interplanetary missions to Mars. The mantra at home and at work, one forever linked to him throughout his life, was the ebullient “Onwards, to Mars!”

In June 1922, Tsander quit his job at the factory to devote all his time to developing a working design of a spaceship that incorporated elements of an airplane. Unemployed, he survived by the generosity of his former fellow factory workers who organized a pool of donations to help feed the man. While they may not have shared Tsander’s unyielding belief in the possibility of space travel, they were extremely fond of Tsander. In gratitude, Tsander gave a speech at the factory, about a year after he quit, in April 1923, which is preserved in the archives of the Russian Academy of Sciences:

Comrades! I’ve been told by the Secretary of your factory committee … that you have awarded me a gift of one percent of your April wages to be presented at this general meeting! Comrades! You yourselves are not living under the best of conditions, and I therefore am even more grateful to you to understand the project on which I am working. I hope also that the money which you have given me will not be in vain, but will make it possible for me to present something of value to your factory…8

To the bemused attendees, Tsander presented in great technical detail the design of an aerospace plane that could fly to other planets and then return to Earth. But most importantly, he touched on the rationale for doing so: “[A] flight around the Earth would have tremendous significance [and] we could probably construct a habitation in which living conditions would be much better than on the Earth…”9 He displayed a deep concern for those who were the weakest in society, including “senior citizens [who] will find it much easier to maintain health in [space].” Speculating about possible civilizations on Mars, he spoke of the “inhabitants of Mars… [whose] inventions could help us to a great extent to become happy and well off.” Tsander concluded with a final note of hope and empathy, of “[a]stronautics, [which] more than the other sciences, calls upon man to unite for a longer and happier life…”10 Happiness was central to his technical vision.

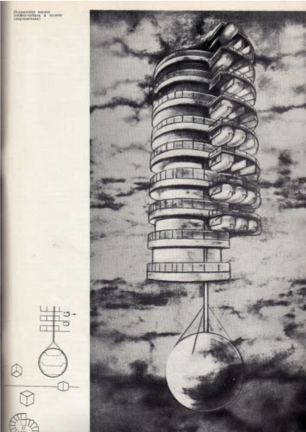

These themes—generosity, sharing, and empathy as part of the human movement to space—suffused much of Tsander’s thinking in the 1920s as he produced a startling body of technoscientific work. Tsander was not a scientific dilettante; in fact, he had a masterful grasp of complex mathematics and was full of ground-breaking ideas. In his research and in public talks, he compared the properties of various propellant combinations and considered the heat processes, aerodynamics, and engineering behind building rocket engines. He was one of the first to propose using light pressure on sails in deep space to accelerate spacecraft, an idea that was finally realized in 2019 by a Japanese spacecraft.11 He also wrote about the possibility of gravity assists for interplanetary flights. He established that one of the most important weight penalties in designing such a spaceship would be the huge mass of fuel that it would have to carry. In order to circumvent this problem, Tsander proposed an idea, radical even today: the space rocket engine would use the melted aluminum parts of its own fuselage as fuel for the engine, in combination with either liquid hydrogen or liquid oxygen. The remaining unused portion of the spaceship would then either go into orbit around the Earth or fly to the other planets.12

Despite his unbridled enthusiasm, Tsander’s life was not easy. He sought unsuccessfully to publish his materials in official Soviet journals. He and his family lived a life of precarity for most of the 1920s. His vision of spaceflight as a project of empathy and compassion was coerced into rational-minded state imperatives when he joined up with a fellow group of space enthusiasts, the Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (GIRD) in the early 1930s. For them, he designed the first liquid propellant rocket engine built in the Soviet Union, which was flown in 1933.

But Tsander wasn’t around to see it. Because of overwork and poor eating habits, he became so emaciated that his boss at GIRD, Sergei Korolev, asked him several times to take a vacation at a sanatorium in Kislovodsk. Eventually, Korolev took 1,300 rubles from GIRD’s budget and just gave it to Tsander for a train trip. In the spring of 1933, Tsander finally departed for the Central Asian resort city of Kislovodsk, known for its clean natural mineral water. Soon after he got to his destination, he fell ill and was taken to a local hospital where he was diagnosed with typhus, which he apparently caught by traveling on third-class rail to save money. In the hospital, he fell asleep and never regained consciousness.

Tsander died in the early morning of March 28, 1933, at the age of forty-six. The last letter he wrote to Korolev ended, “Forward, comrades, and only forward! Raise the rockets higher and higher, closer to the stars.” When they received news of his death, many GIRD members, including Korolev, openly wept for their fallen comrade. Tsander, the dreamer, left behind 7,200 pages of technical writings on almost every aspect of space exploration and rocketry, much of which remained unpublished.

Act III: Babakin’s Hands

The very first human object that touched Mars was built in a factory in Khimki, a suburb of Moscow that was originally established as a settlement in the mid-19th century. By the time of the Revolution, about 2,000 people lived here, in picturesque houses, some evoking the Art Nouveau style fashionable in Russia at the time. The Bolsheviks set about locating a number of industrial cooperative artels in Khimki, including factories building knitwear underwear, furniture, and metal products. In 1937, the area changed when the Soviets established Factory No. 301, a fighter aircraft design and production facility, bringing an influx of about 20,000 people—workers and their families—into the settlement. These men and women were at the forefront of the war: when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, the closest they came to Moscow was Khimki. The people there always considered themselves the last defense against fascism.13

In the 1950s, Khimki became a massive center for defense enterprises with design and production facilities for rocket engines and missiles, the latter of which were designed at Factory 301. After a period of transformation under Nikita Khrushchev, 301 was renamed the Lavochkin enterprise after its late founder Semyon Lavochkin, and in 1965, it inherited the design of lunar and planetary spacecraft from the organization of legendary Soviet chief designer Sergei Korolev. Having decided to focus only on cosmonaut flights, Korolev divested himself of all his other programs and farmed them out to other organizations such as Lavochkin. From 1965 on, everything the Soviet Union launched—to Mars, to Venus, to the Moon—for the next quarter of a century was designed and built at Lavochkin.

If there was one person at Lavochkin who embodied its oddball creative spirit, it was Georgii Nikolaevich Babakin, the design chief who was nominally responsible for the peculiar form of many of the space probes coming out of Khimki. Like Tsander, Babakin was known as “a very gentle person, with a markedly polite manner of addressing people” and like Tsander his life was cut short suddenly.14

Babakin had little formal education and his “natural genius” for spacecraft engineering came from some deeper ineffable instinct. He dropped out of school in 1929 while in the 7th grade, and later completed a four-month radio technician course when he was 16. He received his college degree when he was 42, in 1956. As a self-taught person, he continually surprised his more educated colleagues with engineering solutions that seemed to emerge fully formed. But he also trusted his engineers completely and would organize, within the world of socialist work, small-scale competitions among different engineers. One project, for example, reduced the weight of a spacecraft, promising monetary bonuses for those who were able to lessen a system’s mass by a kilogram or more.15 Babakin joined the Communist Party in 1951 and seemed to accept its tenets—especially workers’ rights—without cynicism. Although he was the nominal head of the Lavochkin design bureau, Babakin had an unusual affinity for the rank-and-file workers, often helping them do manual labor when it would have been considered beneath someone with the rank of “Chief Designer” to do so.

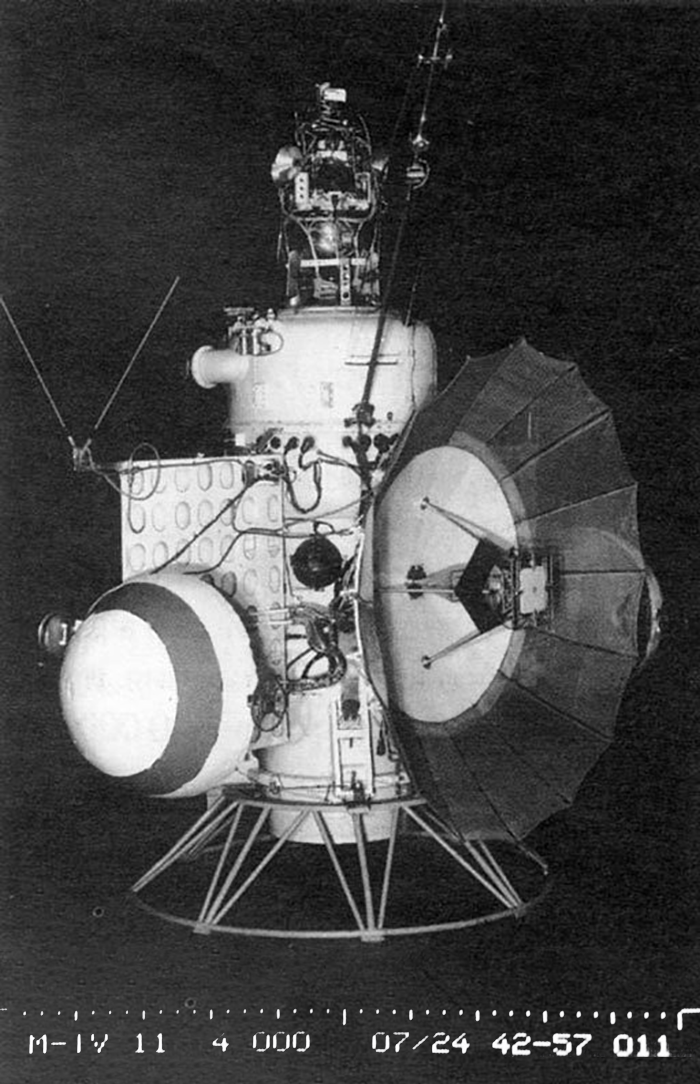

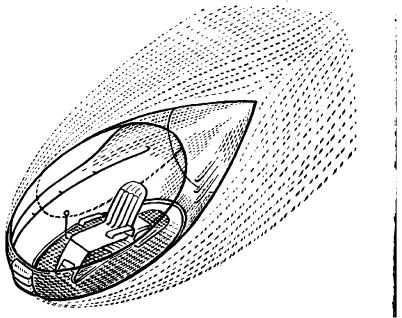

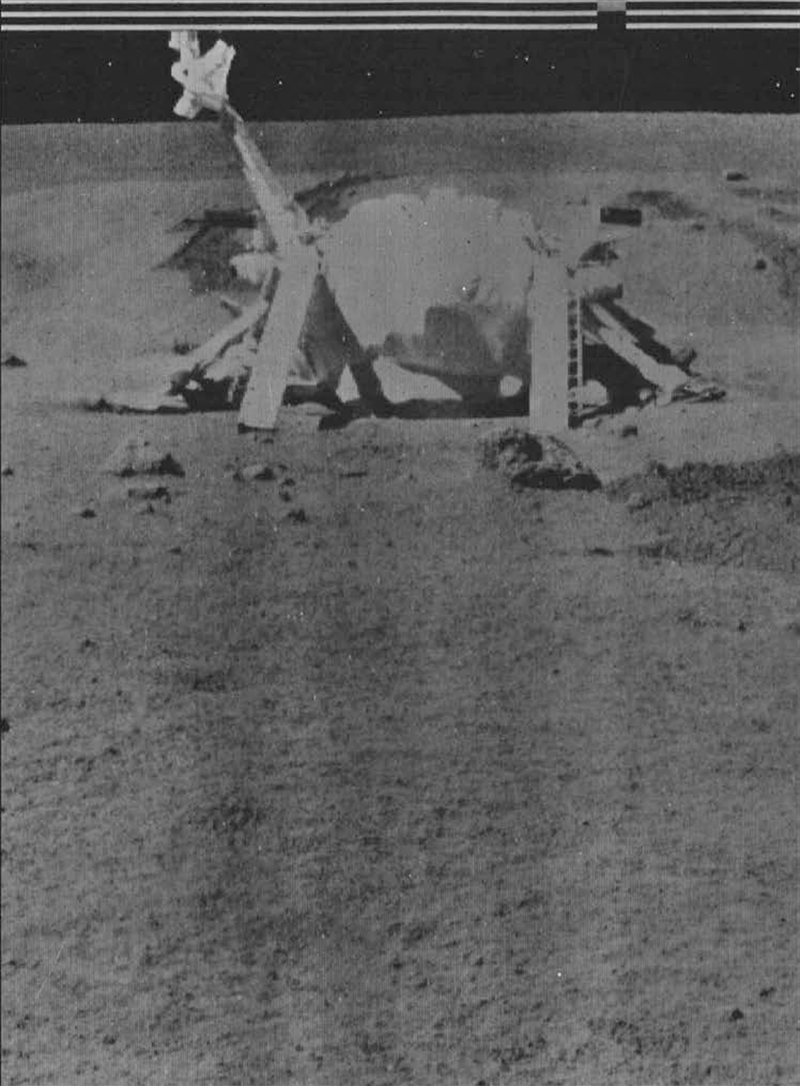

In 1968, Babakin’s team was tasked with the design of a new generation of space probes to visit Mars. They produced two Martian orbiters—if successful, they would become the first spacecraft to orbit another planet—but both were destroyed in 1969 when their launch vehicle exploded. For the next launch window in 1971, Babakin and his engineers devised landing capsules, shaped like the body of a spider, that would alight on Mars, open its petals, and deploy instruments on its surface. Each lander also carried a nine-pound metallic box-shaped robot called PrOP-M that would undulate across the surface on skis, like a box on collapsing stilts. Connected to the lander by an umbilical cord, the device could wander at least 50 feet away from its host while checking the density of the Martian soil and measuring radiation on the surface. It was even programmed to stop and change direction if it ran into an obstacle.16

Mars-2 arrived at Mars on November 27, 1971, but because of an incorrect reentry angle at which it entered the planet’s atmosphere, it plummeted to the surface without any parachute and was destroyed upon impact. Still, it was the first very first object made by humans to make contact with the red planet. Mars-3 landed five days later and transmitted back 70 lines of a haunting image before succumbing to the elements. Because of a violent dust storm that raged across the planet, a coronal discharge may have shorted the electrical instrumentation on the lander.17 An engineer working on the mission, Anatolii Perminov, later wrote that the image showed only “a gray background with no details.”18 For decades experts have examined this image in the hope of discerning any details.

Less well-known is that a few days before the launch of each probe, both were sterilized to ensure that they would not take terrestrial organisms to Mars. But before that procedure, Babakin had walked into the clean room and ran his hands over the smooth metallic sheen of the lander. He was the last human to touch these artifacts before they themselves touched Mars. Sadly, Babakin never knew if these spacecraft ever reached their destinations. In the last months of his life, he had looked unusually tired. At the end of July, he began to cough. At an outpatient clinic, the doctor identified the cough as symptomatic of an acute respiratory infection. A few days later, on August 3, 1971, four months before Mars-3 landed on the red planet, he collapsed at his home and died, apparently of a blood clot. He was 56.19

After Mars-2’s crash landing and Mars-3’s short lifespan, the Soviet Mars program faltered. There were further attempts to reach Mars in 1973 but they were largely unsuccessful. In 1975, NASA’s two Viking Landers arrived on Mars and sent back vivid and beautiful pictures of the surface of the Moon, although the suite of experiments to detect the presence of life was inconclusive. After a long interregnum in the 1980s, another path to Mars eventually opened up, spearheaded by NASA’s many intrepid rovers and orbiters, and eventually, a Tesla flying past the orbit of Mars.20 The static noise of the first Mars-3 image was consigned to a footnote in the history of Mars, while the PrOP-M robot represented a design lineage long forgotten. Human’s first handiwork, touched by Babakin, lay inert on the surface of Mars, alone, silent. Did it ever even exist?

Coda: Netti’s Red Star

Netti woke up after a fitful sleep, ready to make the last jaunt to her destination. Her mind was a jumble of thoughts. Bogdanov’s socialist utopia on Mars. Tsander’s vision of a philosophy of kindness on the red planet. Babakin’s ambition to bring back the first photograph of the surface of Mars. But most of all, she wondered what brought her to this point: was it just that photograph, or was it something deeper, ineffable, and primal? Had there been no alternative to the current moment? With a spider’s web of corporations stretched across Mars poking its terrain, sucking up its life force, and releasing its waste into the void—did it matter that others had dreamt of an alternative? Could there have been a different history? Or even, a different future?

She reactivated the rover’s systems, methodically ran through a checklist, and then, armed with a book, a picture, and a postcard, set off in a southward direction. Her destination was the Ptolemaeus Crater, named after the Greco-Roman thinker Claudius Ptolemy where Mars-3 lay dead.21 This was going to be a long voyage and one she would never come back from, but she had prepared well. She had studied maps, reference books, and pored over old Russian books to find the exact spot where Mars-3 had come down. She could already anticipate driving up to it, the dot slowly becoming larger, perhaps covered in a layer of dust, the vertical camera peeking out from the probe. Would the PrOP-M robot be deployed? Perhaps. She imagined herself exiting the rover in her suit, walking over to the probe, and kneeling down to where the camera was. She would angle her neck to see what the camera saw. What would she see? Hard to know. All she knew was that there was a connection to be made, one haunted by Bogdanov and Tsander and Babakin and now leading to her. A secret future history of Mars awaited her.

“Haunted on Mars” is a secret history in three parts, drawing from real-world events. But like the dreams of the protagonists of each act’s stories, it also offers speculation about the future derived from accreted histories of the past. Each vignette—of Bogdanov, Tsander, and Babakin—represents a moment when the push for exploration of space seemed impossible to stop but then lost its way or disappeared; stray fragments then drift forward as haunted fragments and reconstituted in previously illegible forms. Netti speaks as one both haunted by the foreclosed past and one who herself will haunt our open future, inviting us to imagine a new and better world out there.

The garbled image from Mars-3—ambiguous, mysterious, unclear—perfectly embodies many of the deeper instabilities of this now-mostly-forgotten moment on Mars, the first time that something humans had built, and had made it all the way to the Martian surface in working order. Created in a factory outside of Moscow, this object, officially known as Mars-3, carried with it a possibility of a different future in space, one that was extinguished, much like an extraterrestrial dust storm, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and replaced, it seems now, with another seemingly monolithic vision of outer space, driven by billionaires picking at the distended remains of late-stage capitalism.

The Mars-3 landing, on December 2, 1971, its moment of success interrupted by its sudden moment of loss of contact, points to the kinds of irruptions immanent in the history and future of space exploration—the points at which certain possibilities are foreclosed, others opened, and sometimes closed off again. That the very first human-made object to make contact with Mars—made in a factory in the Moscow suburb of Khimki by workers whose cultural references, speculative worlds, and ideological sensibilities were completely at odds with our contemporary dominant narrative that links capitalism with space travel—presents an odd form of incongruency, like a piece of a puzzle that doesn’t quite fit. The narrative of Mars in the popular imagination, at least in the West, has emerged from the promises of classic science pulp fiction in the early 20th century with a detour through the kitsch of B-movies of the 1950s. More than any other planet, Mars occupied a central place in the Western cosmic imagination—either as a graveyard for past life or as a stage for a screenplay of the future—that is a colorful symbol of aspiration whose power rested on its adaptability to the vicissitudes of the human imagination. In the 2020s, these had seemingly coalesced into the garish vision of a Tesla car hurled into space to fly past the red planet.22 The future of humans on Mars, we are told, will be a merger of Bay Area techno-libertarianism driven by dreams of massive terraforming.

The late writer and critic Mark Fisher famously opined that we are stuck in a form of “capitalist realism”—the pervasive feeling produced by capitalism that there is no “real” alternative to capitalism, one that limits the possibilities for both theory and praxis, but most insidiously constricts even dreams of alternatives, allowing instead minimal gestures that fix the edges while leaving the center unchanged.23 Our collective dreams of exploring space too seem to have arrived at a moment when it appears impossible to imagine alternatives. Already, SpaceX has launched nearly 5,000 of its own Starlink satellites into orbit as of this writing with a total of 42,000 supposedly still-to-be launched by the time the system is completed. What kind of alternative can we imagine when the entire night sky that humans have been gazed at for millennia will be held hostage to the whims of a boy-child whose horizon is as limited as his imagination?

Alternatives to the official future have always existed. The Mars-3 moment reveals an abandoned world in the history—and the future—of space exploration. To appropriate the term made popular by Greil Marcus, the path both backwards and forwards from Mars presents a “secret history” of space travel in the 20th century, one that connects a seemingly disconnected “tradition of shared utopias, solitary refusals, impossible demands, and unexplained disappearances.” In his Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century, Marcus offers a provocation:

Is history simply a matter of events that leave behind those things that can be weighed and measured—new institutions, new maps, new rulers, new winners and losers—or is it also the result of moments that seem to leave nothing behind, nothing but the mystery of spectral connections between people long separated by place and time, but somehow speaking the same language?24

These moments, that “seem to leave nothing” behind are the molecules of the story I present here, which offer a refusal, in narrative form, to the dominant narrative of Mars.25 These molecules haunt the life of our protagonist, Netti, who lives and works on Mars in the year 2036 when other futures seem no longer possible or at least deeply compromised by the monopolizing decay of late-stage capitalism.

In revisiting the notion of “hauntology,” the late writer and critic Mark Fisher asks us to consider the persistence of things that continue to resonate without actually existing. Fisher’s admonition that “[e]verything that exists is possible only on the basis of a whole series of absences, which precede and surround it, allowing it to possess such consistency and intelligibility that it does,” haunts our received stories about Mars.26 The picture sent back by Mars-3 perfectly embodies this hauntological aesthetic, both in the strange melancholia it embodies but also in the “noise” in the image. Such noise, like the “surface noise made by vinyl… makes us aware that we are listening to a time that is out of joint.”27